This cocktail first appeared in print in Jerry Thomas’s legendary book “How To Mix Drinks or The Bon Vivant’s Companion” from 1862. The book, that also goes by the name “The Bar-Tender’s Guide” is regarded to be the first ever cocktail book, or at least the first book entirely dedicated to cocktails. At the time of printing the cocktail had been around for just two years. It was in all likelihood created as a tribute to the first Japanese Diplomatic Mission to the United States. After arriving in San Francisco the mission visited Washington DC before coming to New York where they stayed at the Metopolitan Hotel just a block away from Jerry Thomas’s Palace Bar on 622 Broadway.

One of the members of the delegation was a 17-year old translator called Tateishi Onojirou Noriyuki, who everyone in the US simply called Tommy. Thanks to cocktail historian David Wondrich, we know that a reporter from the Minneapolis Tribune followed the delegation’s trip making Tommy into something of a darling to the media. He really enjoyed the western lifestyle, including cocktails, and apparently he was a bit of a ladies man.

The Japanese Cocktail is one of the few cocktails that are known to be created by Jerry Thomas, often called “The Professor” for his ability to cater even to the most demanding customers. Being known for his showmanship he traveled around the United States only using solid silver bar tools and cups decorated with precious stones.

Jerry Thomas’s creation, the Blue Blazer, was definitely his most spectacular. It is made from a blend of whiskey, sugar and boiling water that he set ablaze and then poured between two tankards while on fire. A show that set The Professor apart from his competitors.

THE DESIGNER

The glass is actually a wooden sake cup called Tohka Souen, designed by Masaharu Asano.

Day Drinking In Disguise

The Tokyo Kaikan (meaning Tokyo Meeting Hall) was built in 1921, facing the Imperial Palace. It soon became a favorite spot for the city’s corporate elite with its restaurants, ball rooms and meeting rooms. The bar had five bartenders on its staff during the 1920s.

From the surrender of the Empire of Japan in September of 1945 until the Treaty of San Francisco in April of 1952, Japan was occupied and administered by the Allied Forces. During this period the Tokyo Kaikan functioned both as the US military officer’s club and as the Tokyo American Club for expatriate businessmen. With the influx of American soldiers the Kaikan soon went from five to forty bartenders on the payroll serving up to 1000 customers per day.

During the post-war occupation, people of Japan were living under hard conditions and rations while some of the American troops spent their free time in the bars of Tokyo. Overseeing the occupation was Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, US General Douglas MacArthur. Entering the bar at the American Club in Tokyo in April 1949, General MacArthur was horrified to find American soldiers having fancy cocktails long before lunch when the Japanese outside were suffering.

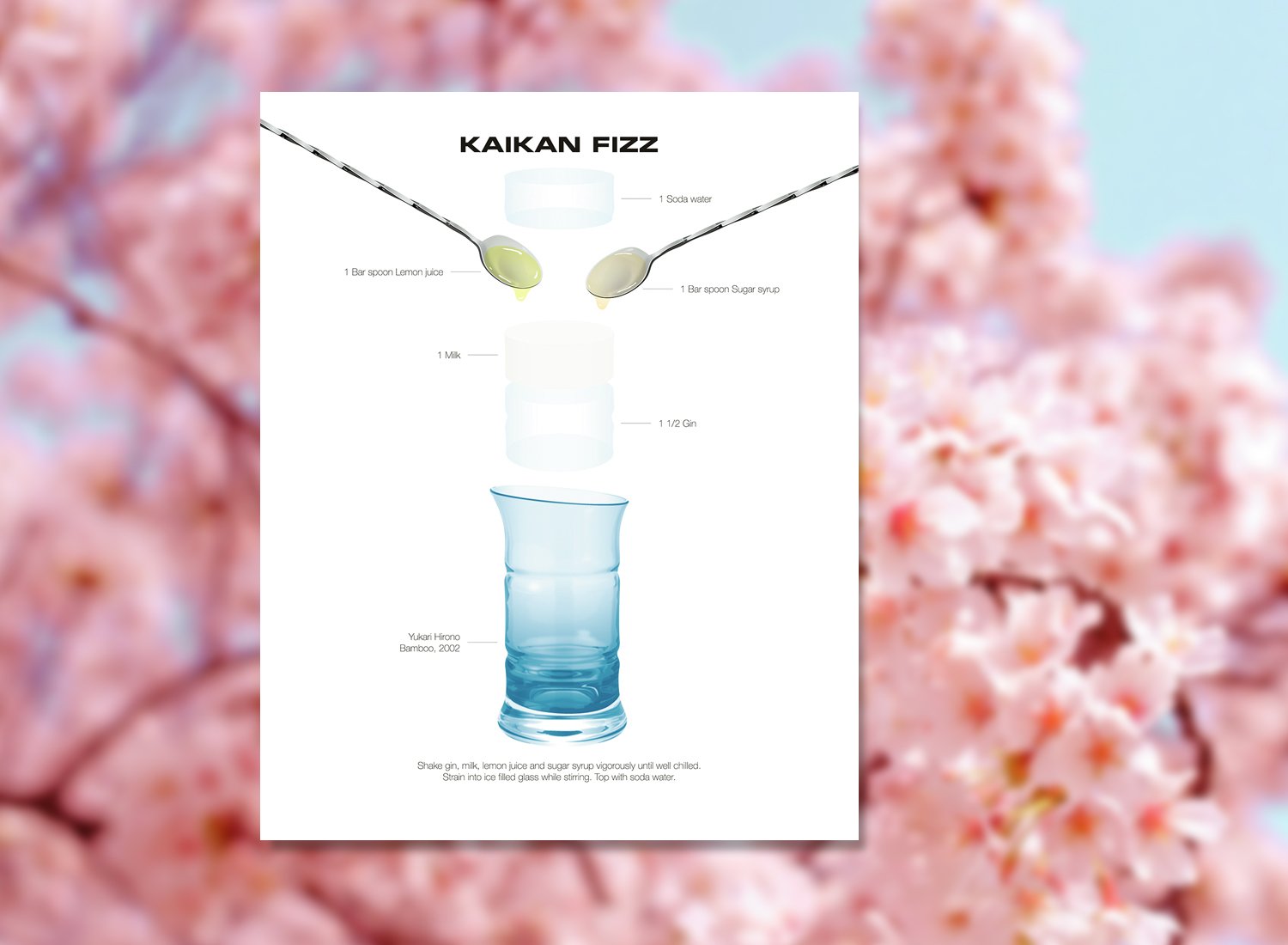

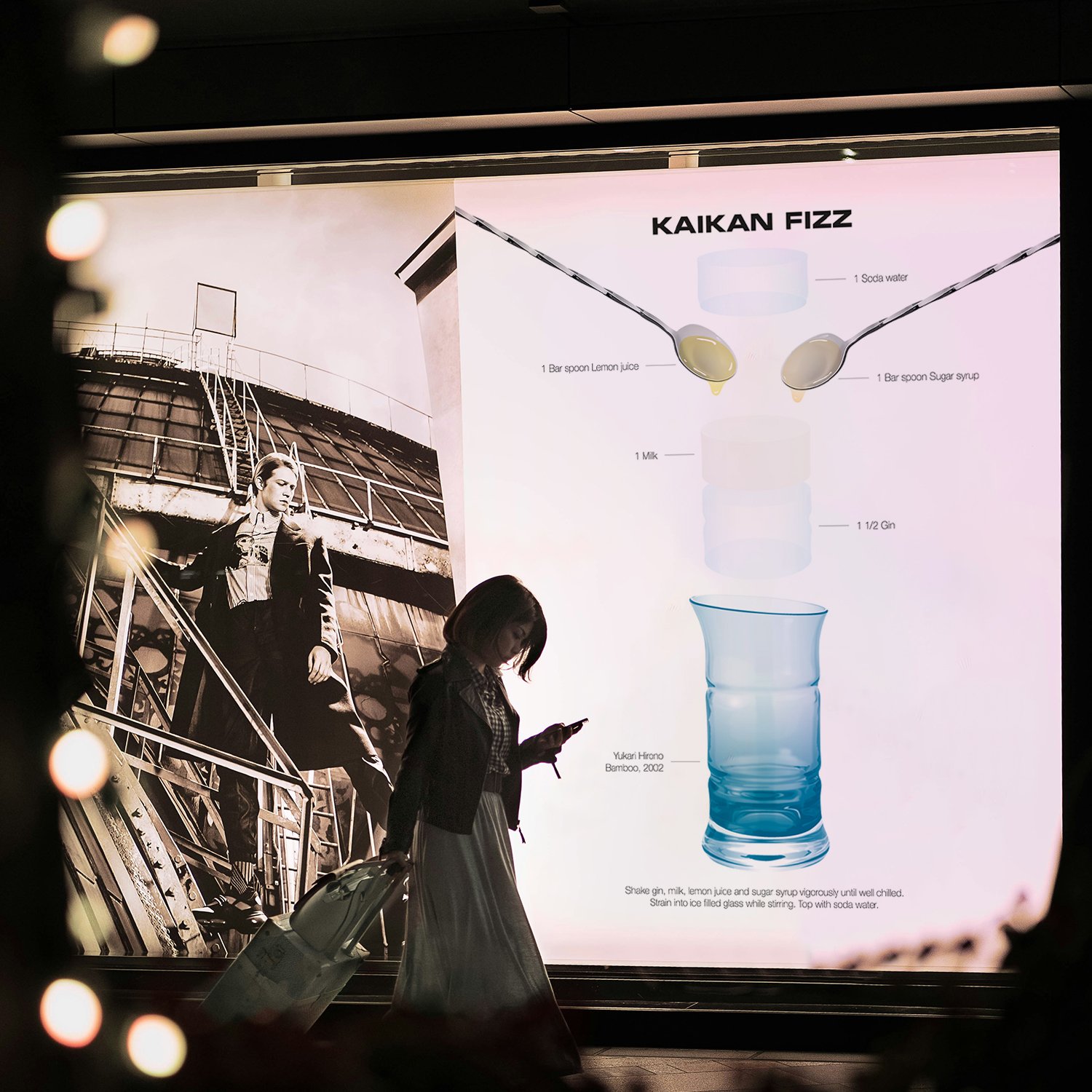

After reprimanding his troops the American party stopped. That is until a crafty bartender, possibly Japan’s most famous bartender, Kiyoshi Imai, who worked the bar at Tokyo Kaikan, had a stroke of genius. He took a regular Gin Fizz, dialed down the seltzer, added an ounce of milk and called it the Kaikan Fizz. This made the drink look like a healthy glass of milk and no general could be opposed to something as wholesome as milk. So the soldiers could go back at it.

When the American troops left Japan in 1952, and the need to hide your day drinking was gone, the Kaikan Fizz had already become a modern classic that has been enjoyed ever since.

The glass called Bamboo was designed in 2002 by Japanese designer Yukari Hirono.

Finally, a tip. When making the Kaikan Fizz, make sure to shake it for a long time to make sure the milk and lemon juice doesn’t curdle. After a vigorous shake, stir while straining it into the glass.

Design For The Masses

In a way the history of the Kikkoman Soy Sauce dispenser, designed in 1961, started at the end of WWII. Kenji Ekuan was born in Tokyo but spent his early years in Hawaii. At the end of the war his family moved to Hiroshima where his father worked as a Buddhist priest. At 16 Ekuan was just released from naval academy when the atomic bomb destroyed Hiroshima and he witnessed the devastation from the train taking him back home. He lost his sister in the blast and his father became Ill with radiation sickness and died a year later.

This tragedy lead him to rethink his career. Instead of following his father’s footsteps he decided he wanted to take part in reshaping post-war Japan through design.

In a later interview he told the New York Times “Faced with that nothingness, I felt a great nostalgia for human culture”. He continued “I needed something to touch, to look at”. “Right then, I decided to be a maker of things.”

In 1952, soon after graduating from the National University of Fine Arts and Music in Tokyo, Mr Ekuan founded his design studio G.K. Design. One of his early assignments came from Kikkoman who wanted him to create a soy sauce dispenser. Up til then soy sauce was bought in big glass bottles and poured into small ceramic dispensers. Due to the particularly high viscosity of soy sauce it, more often than not, dripped along the side of the dispenser leaving a stain on the table.

Kenji Ekuan chose to make a glass bottle so you would know exactly when to refill it, and when you did you wouldn’t spill thanks to its wide mouth. The bigger problem was how to make the cap.

This part of the project ended up taking 3 years. It had to be easy to pour but yet spill-proof. After 100 prototypes Ekuan realized that the best solution was an upward facing spout. The spout design made the last drop flow back into the bottle rather than dripping onto the table.

Released onto the international market in 1961 the Kikkoman soy sauce dispenser became a symbol of new contemporary Japanese design. Ekuan’s goal as a designer was to make design solutions for the masses and with the Kikkoman dispenser he managed to do just that with an exquisite example of Japanese design spread to kitchens all over the world.