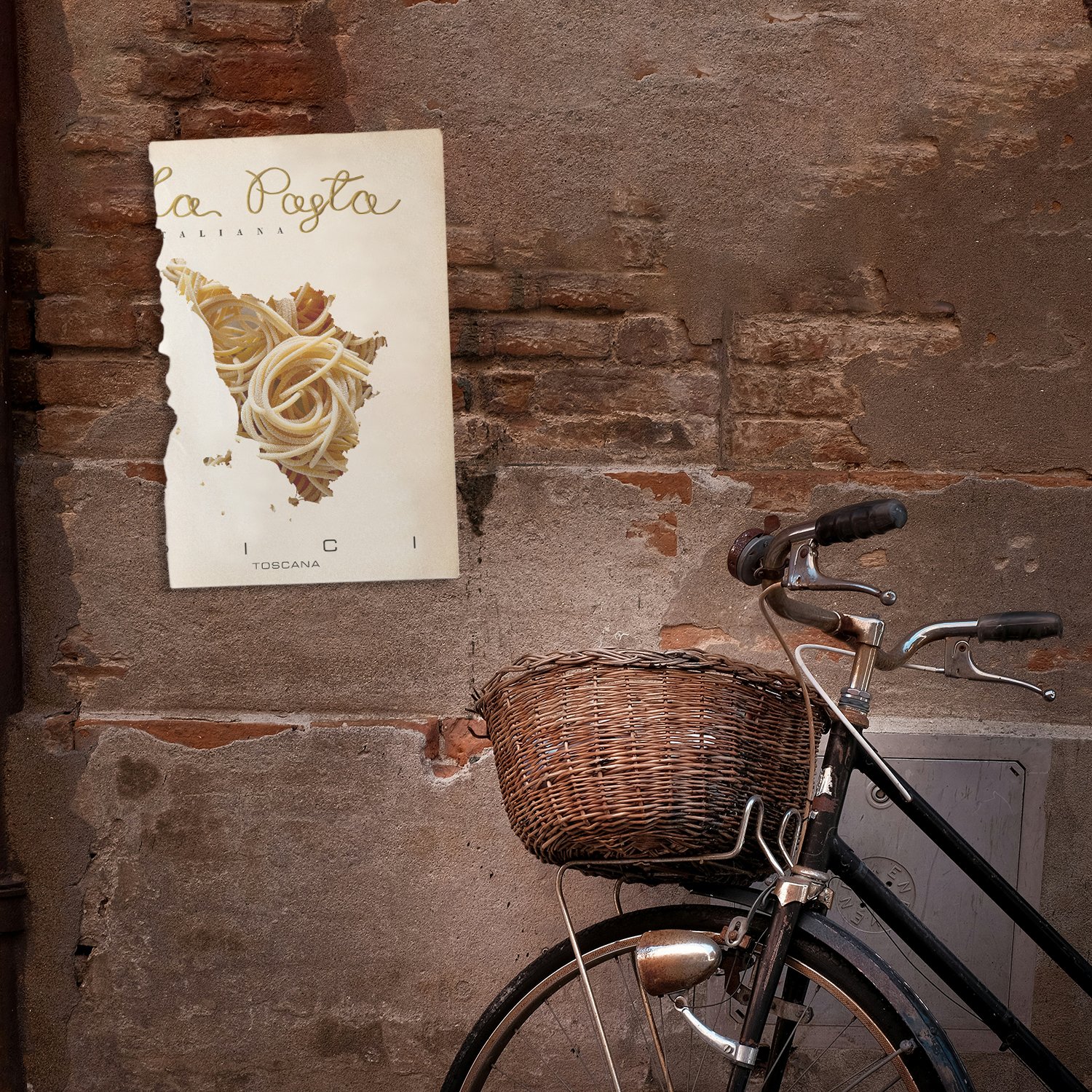

“La Pasta Italiana” is a new exhibition featuring posters with pasta from 8 different regions in Italy. It opens at the Italian Coffee Bar Sempre at Jacobsbergsgatan 5 in central Stockholm.

Join me on Friday October 11 at 5 pm for an aperitivo at the best Italian Coffee Bar in Stockholm.

La Pasta Italiana: Farfalle

The history of the farfalle pasta, meaning butterflies in Italian, dates back to the 16th century in Northern Italy.

Originating in the regions of Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna, farfalle was traditionally made by hand in Italian homes. The pasta is shaped by pinching the center of a small rectangle of pasta dough, giving it its characteristic butterfly or bow-tie form.

Traditionally, farfalle was made using eggs and soft-wheat flour when prepared at home. However, when produced commercially in factories, it is typically made with durum wheat and either eggs or water. The choice of ingredients affects the pasta’s texture and taste, with homemade versions often being richer and more toothsome.

Farfalle comes in various sizes and can have slight variations in design depending on the region. Some versions may have flat edges all around instead of the iconic fluted sides. The versatility of farfalle has made it a popular pasta shape worldwide, suitable for both hot dishes with sauces and cold pasta salads.

The process of making farfalle by hand involves rolling out the pasta dough to a thin sheet, usually about 1mm thick. The dough is then cut into rectangles, and each piece is carefully shaped by hand. The center is gently pushed down to create a crease, while the long edges are pulled up slightly and then folded down and pressed to seal the dough together, forming the distinctive shape.

Over time, farfalle has become one of the most recognizable short-cut pasta shapes, loved for its playful appearance and ability to hold sauces well. Its popularity has led to widespread production, with both artisanal pasta makers and large-scale manufacturers offering this charming pasta shape to consumers around the world.

La Pasta Italiana: Rigatoni

The history of rigatoni pasta is a fascinating journey through Italian culinary traditions. Rigatoni, whose name comes from the Italian word ”rigato” meaning ”ridged” or ”lined,” is a tube-shaped pasta with ridges on the exterior.

Originating in central and southern Italy, particularly in Rome and Sicily, rigatoni has been a staple of Italian cuisine for centuries. While the exact date of its invention is unclear, it likely emerged during the late Middle Ages or early Renaissance period when pasta-making techniques were becoming more sophisticated.

The distinctive ridged texture of rigatoni serves a practical purpose. These ridges allow the pasta to hold onto sauces more effectively, enhancing the overall flavor of dishes. This design also makes rigatoni ideal for baked pasta dishes, as it can withstand longer cooking times without losing its shape.

Traditionally, rigatoni was made by hand, a labor-intensive process that required skill and patience. Pasta makers would wrap dough around thin rods to create the tubular shape, then carefully remove the pasta and let it dry. This method ensured that each piece of rigatoni had a consistent shape and texture.

As pasta production became industrialized in the 19th and 20th centuries, rigatoni became more widely available. The invention of pasta extruders allowed for mass production while maintaining the characteristic ridged exterior.

Rigatoni has played a significant role in many classic Italian dishes. In Rome, it’s often served with pajata, a sauce made from veal intestines. In Sicily, it’s commonly used in pasta al forno, a baked pasta dish. The versatility of rigatoni has also made it popular in modern fusion cuisines around the world.

Today, rigatoni continues to be a beloved pasta shape, available in various sizes and even gluten-free versions. Its enduring popularity is a testament to its versatility and the timeless appeal of Italian pasta traditions.

Hear the Sound of Pasta

This very original pasta from the southern Italian region of Puglia, the heal of the boot if you will, is called Orecchiette, “little ears”. It is believed to have originated in the 8th or 9th centuries when Puglia was under Norman-Swabian rule, or Normanno-Svevo in Italian. With the origins this far back in time however, it is very hard to be absolutely certain how the pasta came about. Similar pasta is found both in Provence in France and in the northern parts of Liguria, the home of the Trofie, but the specific shape and the pasta seems to be a very Pugliese thing. Locally, the pasta is said to be made to look like the roofs of the Trulli houses, a very particular type of round, hut-like houses found in Alberobello in Puglia and nowhere else in the world.

The pasta is made without eggs and it is shaped by pressing your thump print into the dough to create a small bowl. This sauce-cup makes a perfect vessel to catch the pasta sauce, traditionally a tomato sauce, “orecchiette al sugo.”

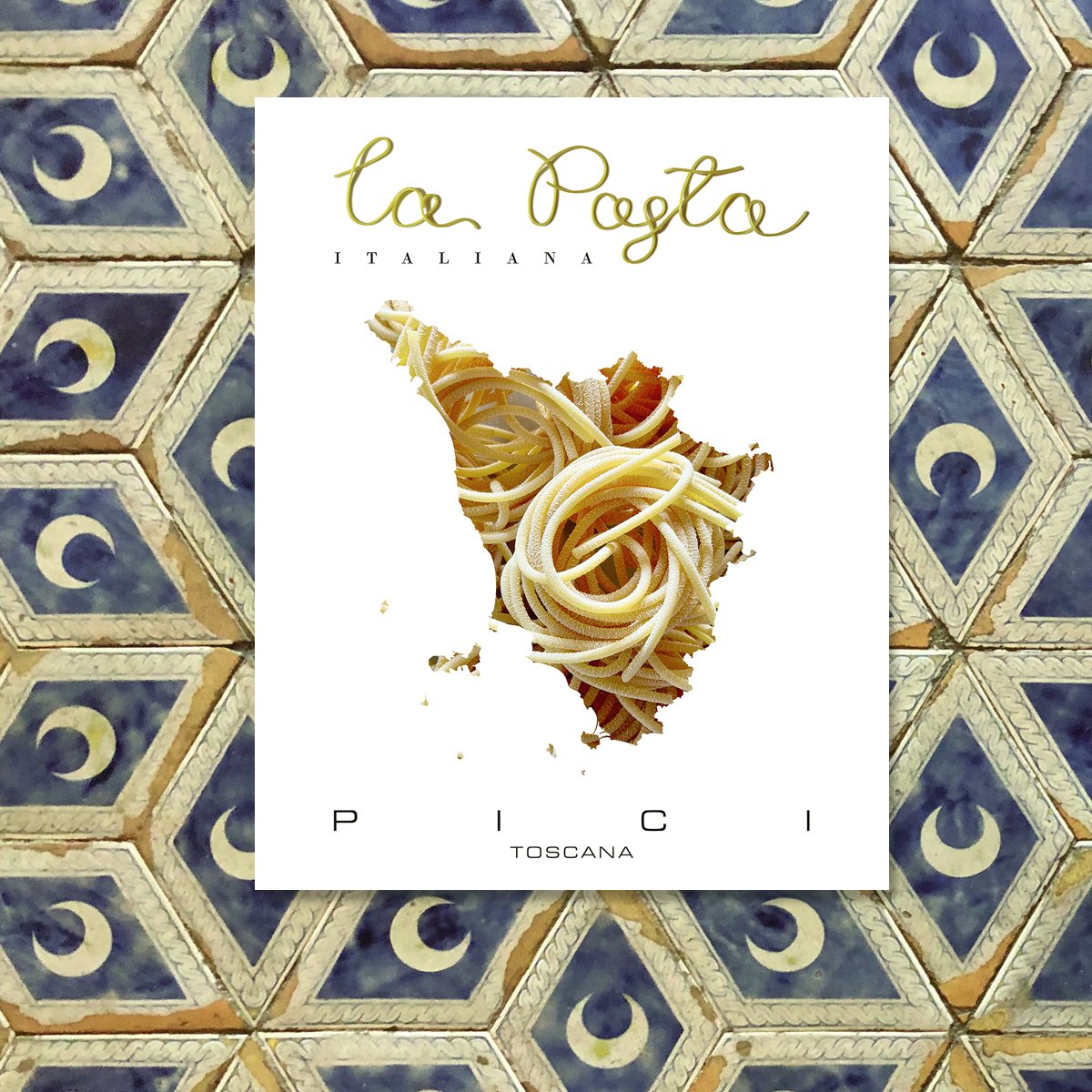

La Pasta Italiana: Pici

Made traditionally with just flour, water and salt, Pici is considered part of the “cucina povera” the poor cuisine, due to its lack of egg. The Pici pasta looks like a long, thick spaghetti curled up in bundles like tagliatelle. This Tuscan specialty is sometimes called “Pici Senesi” as it is believed to originate in Siena. Its roots however, dates all the way back to ancient Etruscan times. A pasta similar to Pici has been found depicted on a mural in the Tomb of the Leopards in Tarquinia, an Etruscan burial chamber from 540-470 BCE (that is technically in Lazio, not in Tuscany). From Tarquinia in the Viterbo region the Pici spread throughout Tuscany.

The rustic Pici has always been considered to be a rural, dish eaten by peasants (as opposed to the royal Mafaldine from Campania). In Tuscany it is often served with Cacio e pepe but one of the most traditional dishes is Pici all’aglione a recipe from the area surrounding Siena. The sauce is made with aglione, (a regional type of garlic), tomato, olive oil and peperoncino. Another typical way of eating the pasta is Pici alle briciole made with thin slices of Tuscan bread, peperoncino, garlic, salt, grated Tuscan Pecorino and, of course, olive oil.

La Cucina Casalinga

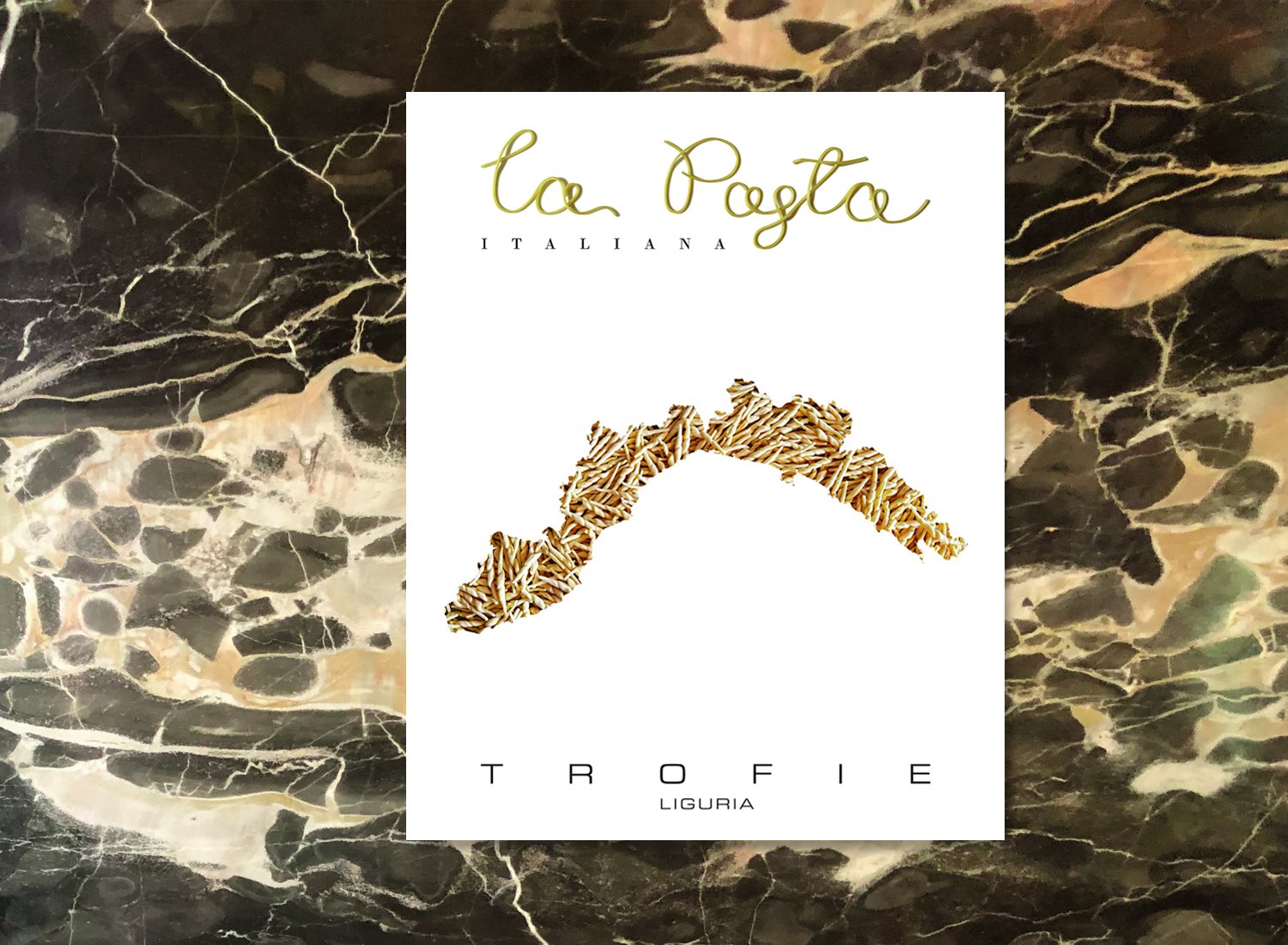

TROFIE

The region of Liguria is basically the continuation of the French Riviera. Known for the picturesque villages called Cinque Terre, (Monterosso, Vernazza, Corniglia, Manarola and Riomaggiore), but also Portofino, San Remo and, of course, Genova. Genova rose to power as a maritime republic in the Middle Ages, dominating trade in the Mediterranean Sea thanks to its prowess in shipbuilding and banking. During the city’s prime in the 16th century Genova rivaled Venice, attracting many artists including Rubens, Caravaggio and Van Dyck. Still to this day the city is filled with more beautiful palaces than they know what to do with, and visiting the city you often stumble upon incredible 16th century frescoes in shops, restaurants and bars. Liguria is also known for its pasta.

The pasta of choice in Liguria is the Trofie, a type of pasta originating in the Ligurian cities of Recco, Sori and Camogli m, on the so called Golfo Paradiso. This short pasta is made by hand rolling small pieces of dough, creating tapered ends. Then twisting the pasta into its final shape. It is thought that it was originally made from leftover dough from other types of pasta, rolled by fishermen’s wives while waiting for their husbands to come back from sea. The name probably comes from the Ligurian verb strufuggiâ meaning ‘to rub’ or ‘to twist’ which is essentially the technique used for making the pasta.

The Trofie didn’t make it to the port city of Genova until the mid 20th century but has since then been the go to pasta when making a Pesto alla Genovese in Genova always eaten with potatoes and green beans that are cooked together with the trofie. By the way, the best place to have a real Trofie col pesto alla Genovese is at the fabulous Trattoria da Maria in a back alley in Genova. Not fancy at all but this is a great place to have original Ligurian Cucina Castling.

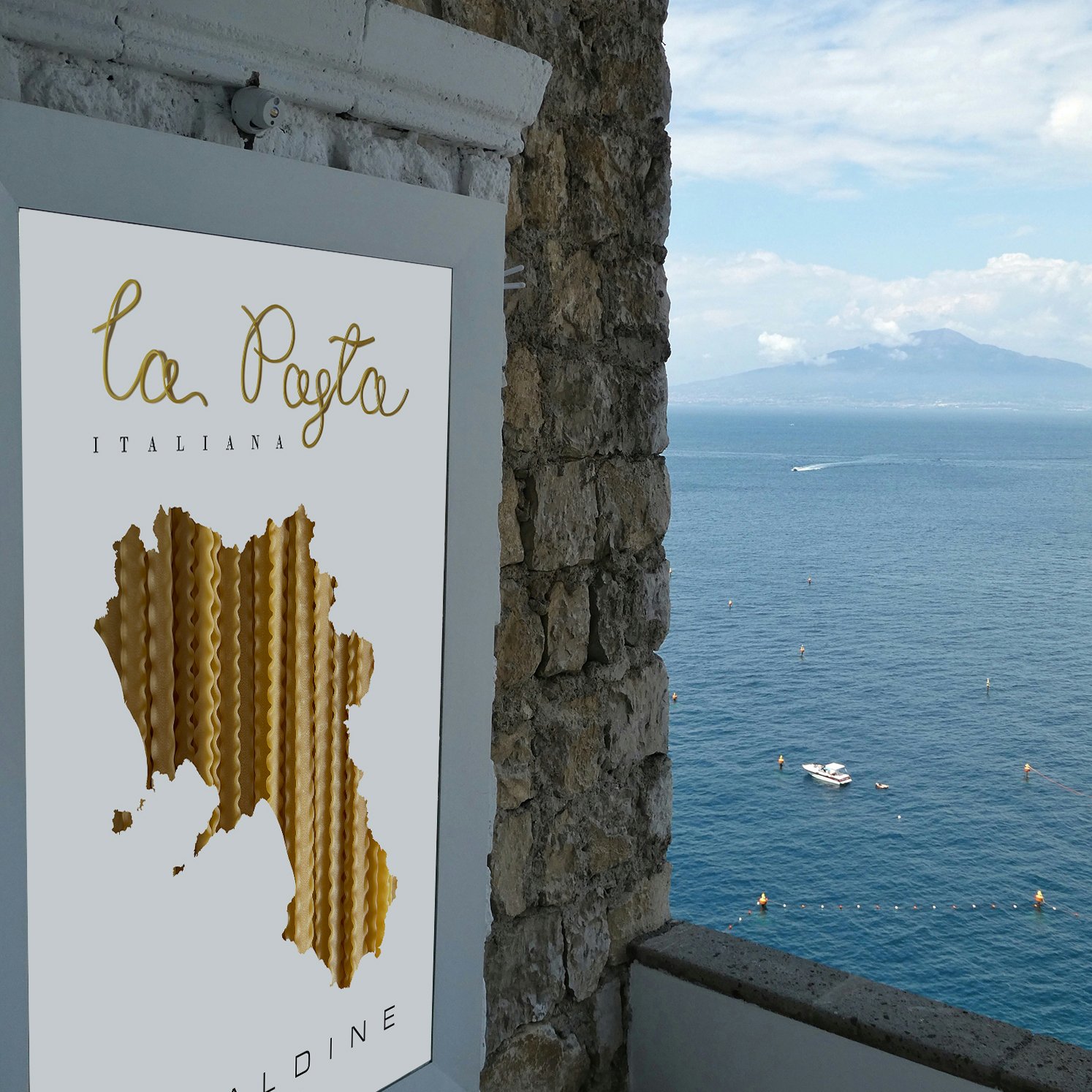

Welcome To the World of Pasta

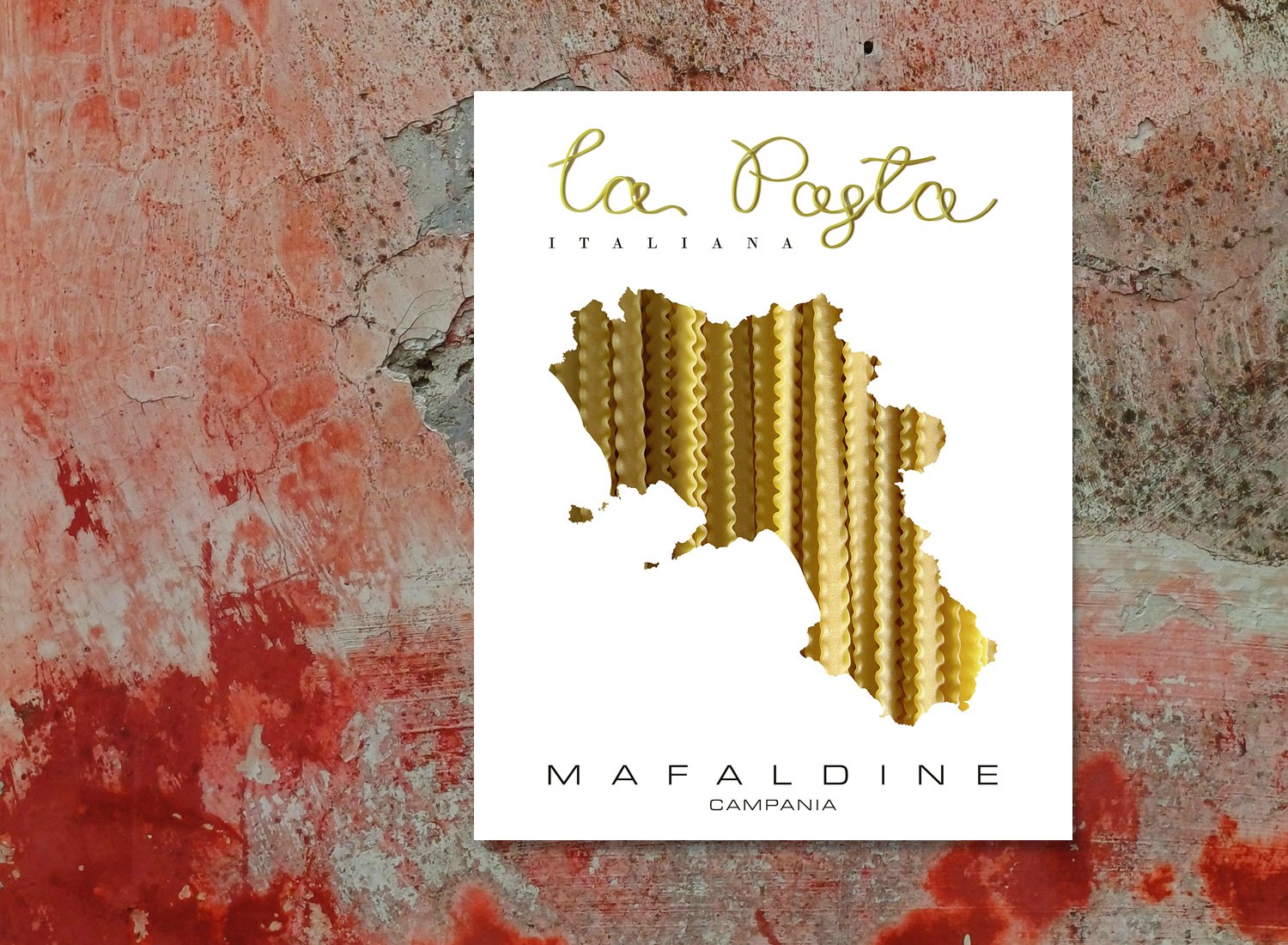

Here is the first in a brand new series of original artwork. This time we’re taking on the fabulous world of Italian pasta, one (or possibly more) from every Italian region, because all regions has their very own special pasta, fitting perfectly with their particular sauces. For instance Trofie from Liguria on the Italian riviera, that fits like a glove with the Pesto Genovese. For the first in the series however, we’re traveling down to Napoli and the region of Campania to try their pasta fit for royalty, the Mafaldine.

Mafaldine was originally called Fettuccelle Riccie and was created in Naples, next to one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world, Mount Vesuvius. When Princess Mafalda of Savoy, the daughter of Italy’s King Vittorio Emmanuele III and Queen Elena of Montenegro, was born in 1902 the royal baby was honored by changing the name of the pasta to Mafaldine. Princess Mafalda happened to have wavy curly hair just like the the pasta, so the pasta fitted her perfectly.

On a side note, to honor the occasion of the royal wedding between Vittorio Emanuele and Queen Elena, specifically to honor Queen Elena of Montenegro, amaro maker Stanislao Cobianchi changed the name of his Elisir Lungavita to Amaro Montenegro. Still today you will find Amaro Montenegro in most Italian bars.

The Mafaldine is made of 1 centimeter wide pasta ribbons, las ong as spaghetti, with wavy sides that are slightly thicker than the middle part. This to make the sides sturdier, a feature that supposedly enhances the flavor of the pasta and its sause. Because of its royal connection Mafaldine is often used for special occasions, served with ragù or ricotta.

The life of Princess Mafalda however was very tragic. She married a German prince, Philipp of Hesse who worked as a Nazi intermediary between Germany and Italy during WWII. Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels mistrusted the Princess and believed that she was collaborating with the allied forces. Mafalda was arrested and was sent to Buchenwald concentration camp, where she died.