The history of the farfalle pasta, meaning butterflies in Italian, dates back to the 16th century in Northern Italy.

Originating in the regions of Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna, farfalle was traditionally made by hand in Italian homes. The pasta is shaped by pinching the center of a small rectangle of pasta dough, giving it its characteristic butterfly or bow-tie form.

Traditionally, farfalle was made using eggs and soft-wheat flour when prepared at home. However, when produced commercially in factories, it is typically made with durum wheat and either eggs or water. The choice of ingredients affects the pasta’s texture and taste, with homemade versions often being richer and more toothsome.

Farfalle comes in various sizes and can have slight variations in design depending on the region. Some versions may have flat edges all around instead of the iconic fluted sides. The versatility of farfalle has made it a popular pasta shape worldwide, suitable for both hot dishes with sauces and cold pasta salads.

The process of making farfalle by hand involves rolling out the pasta dough to a thin sheet, usually about 1mm thick. The dough is then cut into rectangles, and each piece is carefully shaped by hand. The center is gently pushed down to create a crease, while the long edges are pulled up slightly and then folded down and pressed to seal the dough together, forming the distinctive shape.

Over time, farfalle has become one of the most recognizable short-cut pasta shapes, loved for its playful appearance and ability to hold sauces well. Its popularity has led to widespread production, with both artisanal pasta makers and large-scale manufacturers offering this charming pasta shape to consumers around the world.

La Pasta Italiana: Rigatoni

The history of rigatoni pasta is a fascinating journey through Italian culinary traditions. Rigatoni, whose name comes from the Italian word ”rigato” meaning ”ridged” or ”lined,” is a tube-shaped pasta with ridges on the exterior.

Originating in central and southern Italy, particularly in Rome and Sicily, rigatoni has been a staple of Italian cuisine for centuries. While the exact date of its invention is unclear, it likely emerged during the late Middle Ages or early Renaissance period when pasta-making techniques were becoming more sophisticated.

The distinctive ridged texture of rigatoni serves a practical purpose. These ridges allow the pasta to hold onto sauces more effectively, enhancing the overall flavor of dishes. This design also makes rigatoni ideal for baked pasta dishes, as it can withstand longer cooking times without losing its shape.

Traditionally, rigatoni was made by hand, a labor-intensive process that required skill and patience. Pasta makers would wrap dough around thin rods to create the tubular shape, then carefully remove the pasta and let it dry. This method ensured that each piece of rigatoni had a consistent shape and texture.

As pasta production became industrialized in the 19th and 20th centuries, rigatoni became more widely available. The invention of pasta extruders allowed for mass production while maintaining the characteristic ridged exterior.

Rigatoni has played a significant role in many classic Italian dishes. In Rome, it’s often served with pajata, a sauce made from veal intestines. In Sicily, it’s commonly used in pasta al forno, a baked pasta dish. The versatility of rigatoni has also made it popular in modern fusion cuisines around the world.

Today, rigatoni continues to be a beloved pasta shape, available in various sizes and even gluten-free versions. Its enduring popularity is a testament to its versatility and the timeless appeal of Italian pasta traditions.

La Cucina Casalinga

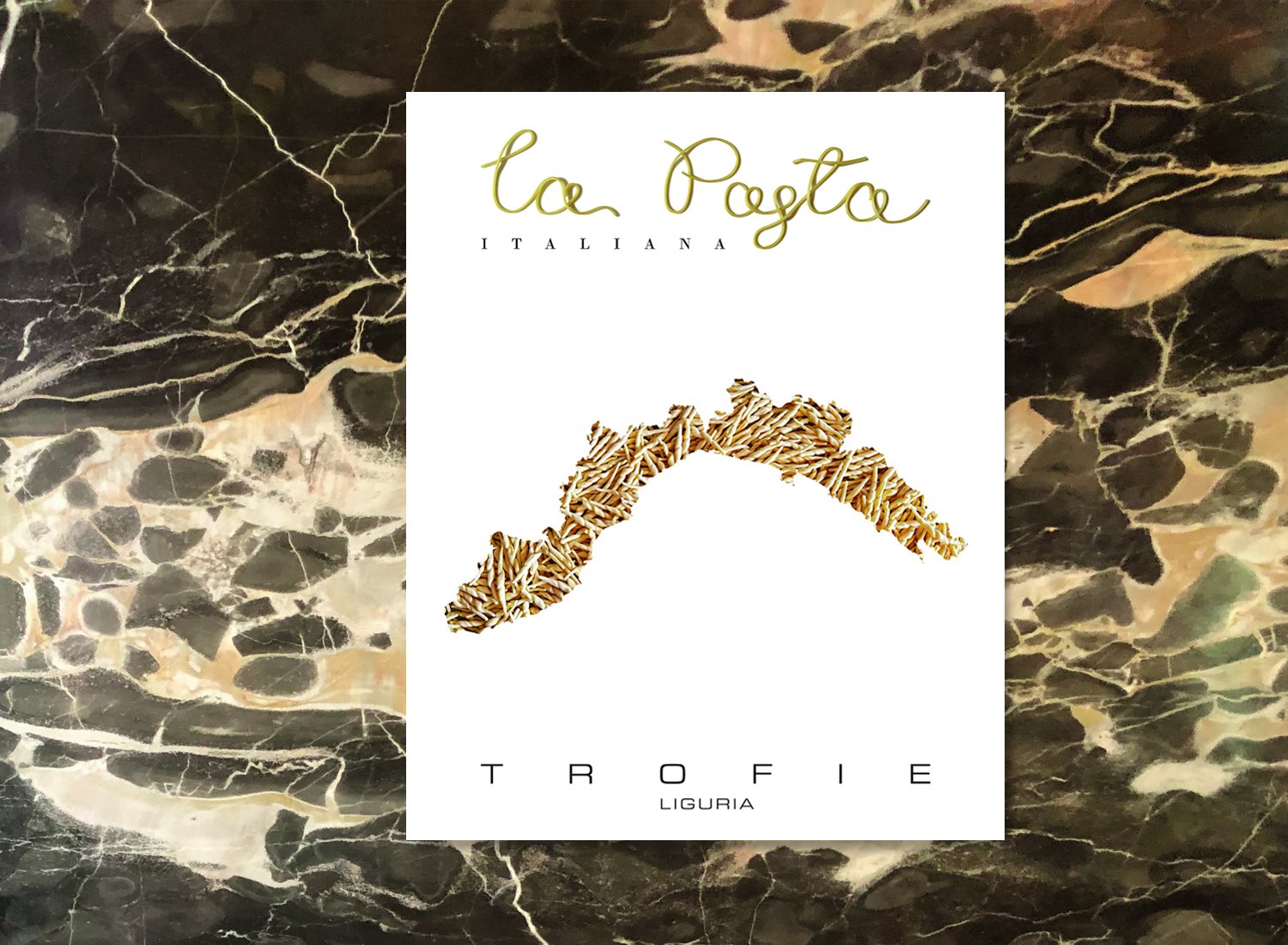

TROFIE

The region of Liguria is basically the continuation of the French Riviera. Known for the picturesque villages called Cinque Terre, (Monterosso, Vernazza, Corniglia, Manarola and Riomaggiore), but also Portofino, San Remo and, of course, Genova. Genova rose to power as a maritime republic in the Middle Ages, dominating trade in the Mediterranean Sea thanks to its prowess in shipbuilding and banking. During the city’s prime in the 16th century Genova rivaled Venice, attracting many artists including Rubens, Caravaggio and Van Dyck. Still to this day the city is filled with more beautiful palaces than they know what to do with, and visiting the city you often stumble upon incredible 16th century frescoes in shops, restaurants and bars. Liguria is also known for its pasta.

The pasta of choice in Liguria is the Trofie, a type of pasta originating in the Ligurian cities of Recco, Sori and Camogli m, on the so called Golfo Paradiso. This short pasta is made by hand rolling small pieces of dough, creating tapered ends. Then twisting the pasta into its final shape. It is thought that it was originally made from leftover dough from other types of pasta, rolled by fishermen’s wives while waiting for their husbands to come back from sea. The name probably comes from the Ligurian verb strufuggiâ meaning ‘to rub’ or ‘to twist’ which is essentially the technique used for making the pasta.

The Trofie didn’t make it to the port city of Genova until the mid 20th century but has since then been the go to pasta when making a Pesto alla Genovese in Genova always eaten with potatoes and green beans that are cooked together with the trofie. By the way, the best place to have a real Trofie col pesto alla Genovese is at the fabulous Trattoria da Maria in a back alley in Genova. Not fancy at all but this is a great place to have original Ligurian Cucina Castling.

Welcome To the World of Pasta

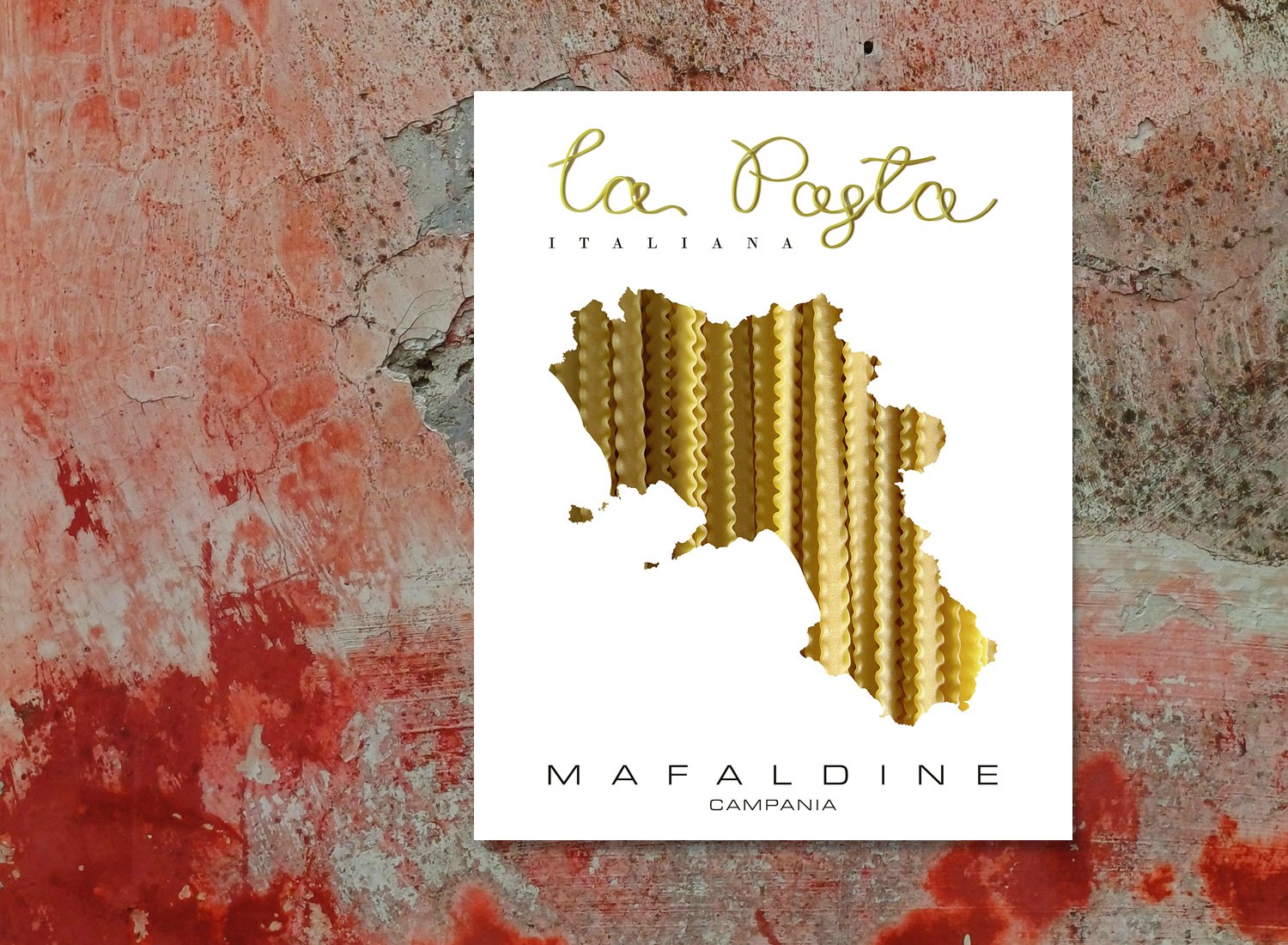

Here is the first in a brand new series of original artwork. This time we’re taking on the fabulous world of Italian pasta, one (or possibly more) from every Italian region, because all regions has their very own special pasta, fitting perfectly with their particular sauces. For instance Trofie from Liguria on the Italian riviera, that fits like a glove with the Pesto Genovese. For the first in the series however, we’re traveling down to Napoli and the region of Campania to try their pasta fit for royalty, the Mafaldine.

Mafaldine was originally called Fettuccelle Riccie and was created in Naples, next to one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world, Mount Vesuvius. When Princess Mafalda of Savoy, the daughter of Italy’s King Vittorio Emmanuele III and Queen Elena of Montenegro, was born in 1902 the royal baby was honored by changing the name of the pasta to Mafaldine. Princess Mafalda happened to have wavy curly hair just like the the pasta, so the pasta fitted her perfectly.

On a side note, to honor the occasion of the royal wedding between Vittorio Emanuele and Queen Elena, specifically to honor Queen Elena of Montenegro, amaro maker Stanislao Cobianchi changed the name of his Elisir Lungavita to Amaro Montenegro. Still today you will find Amaro Montenegro in most Italian bars.

The Mafaldine is made of 1 centimeter wide pasta ribbons, las ong as spaghetti, with wavy sides that are slightly thicker than the middle part. This to make the sides sturdier, a feature that supposedly enhances the flavor of the pasta and its sause. Because of its royal connection Mafaldine is often used for special occasions, served with ragù or ricotta.

The life of Princess Mafalda however was very tragic. She married a German prince, Philipp of Hesse who worked as a Nazi intermediary between Germany and Italy during WWII. Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels mistrusted the Princess and believed that she was collaborating with the allied forces. Mafalda was arrested and was sent to Buchenwald concentration camp, where she died.

Negroni Week is Discount Week

This week is Negroni Week and if you haven’t started already it’s time to stir one up. Preferably using the Alessi Shaker 870 designed by Carlo Mazzeri and Luigi Massoni in 1957. Or buy the Random Things poster with the shaker, why not together with a Negroni poster. If you’d like you can use the discount code NEGRONI for either of the two posters to get 10% off but no pressure, you can buy them without the code as well. Being Negroni Week the code should apply to the Negroni Sbagliato poster as well, and it does.

The Shaker That Conquered the World

The Alessi company was founded in 1921 by sheet metal worker Giovanni Alessi Anghini who set up shop in Omegna, not far from Milan. The company started out making tableware in copper and brass but they soon expanded to coffee pots, trays and other household products. In 1938 Alessi introduced stainless steel and after the war this entirely replaced brass in the production. From the 1930s until the ’50s Carlo Alessi, the son of Giovanni, was head designer but when his younger brother Ettore joined the business in 1945 he made Carlo realize the potential in hiring external designers. One of the first project being designed outside the family was the incredibly successful Shaker 870, created by Carlo Mazzeri and Luigi Massoni in 1957.

Carlo Mazzeri was born in Oleggio, Italy in 1927 and studied architecture in Venice. Just a year after graduating in 1956 he designed the shaker for Alessi with Luigi Massoni. During the 1960s and ’70s he kept working for Alessi alongside Anselmo Vitale, designing a series of products for the hotel industry. Working with industrial construction, Mazzeri also made the new Alessi plant in Omegna in the 1960-1971.

Luigi Massoni was born in Milan in 1930 and this is where he studied at the “Collettivo di Architettura”. One of his first major designs was the Shaker 870 but he continued working with Alessi, creating the Serie 5 containers. Massoni wasn’t just working as an architect and designer, he was also a freelance journalist and in 1959 he founded “Mobilia” a center for the promotion of Italian design. Through the years Massoni kept designing for the home and kitchen working with Boffi and Guzzini.

Through the years Alessi has worked with designers like Achille Castiglioni, Patricia Urquiola, Zaha Hadid, Jasper Morrison and Philippe Starck.

Taking Prints to the Next Level

You might not have either space nor the economy to buy an Italian design classic like Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni’s Arco floor lamp. You might not necessarily have any wall space to get a print from the Italy at Random collection either. But you probably have a sofa, a bed or a favorite chair. What makes that relaxing space even better, well, a double sided throw pillow of course.

You can now get the Random Things collection as a beautiful pillow to light up any space in your home or office, or vacation spot for that matter.

Italy at Random

In a world of Italian design mobilità studio has illustrated a series of products all being part of making Italy into the world leader in design that it is. All products are genuine design icons form the gondola bow iron first mentioned in the 11th century to Cini Boeri’s Ghost Chair made from a single sheet of glass in 1987.

On Friday April 28 you are more than welcome to join me at the Sempre Coffee Bar on Jakobsbergsgatan 7 in Stockholm when the new exhibition Italy at Random opens at 5 pm.

If you have any other designs or random products from Italy (or other parts of the world) that you think should be part of the collection please tell me and they just might find their way onto your wall, a pretty great place to enjoy world class design.

The Little Fridge Car

During the first decade after WWII, war torn Europe was slowly trying to rebuild its economies. Engineer and businessman Renzo Rivolta, the owner of Isothermos, a company that before the war manufactured refrigerators and electric heaters, saw the rising demand for a micro-car. Rivolta was also the owner of ISO Autoveicoli, at the time Italy’s third largest producer of two-wheeled vehicles. Together with two aeronautical engineers, Ermengildo Preti and Pierluigi Raggi he created the first Isetta prototype in 1952. Isetta being the diminutive form of Iso. Legend has it that they actually used a repurposed fridge door for the prototype.

As for the performance, the Isetta, equipped with a motorcycle motor, took 30 seconds to reach 50 kph. This was, however made up by the fact that it fit two adults and was perfect for use in the narrow streets of Italian cities.

To be able to fund other project, like his sports car ISO Grifo, Mr Rivolta decided to sell the license for the Isetta to other manufacturers. BMW was at the time on the verge of bankruptcy and quickly saw the potential of the micro-car. They upgraded the Isetta with a new motor, better suspension and added a sunroof making the car reach a whopping 85 kph. BMW ended up making 10,000 cars during the first 8 months making it more popular than it ever was in Italy.

Apart from Italy and Germany the Isetta was also manufactured in France, the UK, Argentina and Brazil and has had such an influence on the automobile industry that it inspired the creation of the Smart Car in 1998.

Picking Italian Mushrooms

Massimo Vignelli was born in Milan in 1931. At the age of 14 he decided he wanted to be an architect and at 16 he started working as an architectural draftsman before attending Università di Architettura in Venice. Here he met his future wife and business partner Lella Vignelli, herself coming from a family of architects.

In 1956 Massimo Vignelli was commissioned by the already famous glass maker Venini to design a series of lamps. The company had already worked with Italian designers like Carlo Scarpa and Giò Ponti. This project was initially called 4040 Zaffiro a name that was later changed to Fungo thanks to the lamps mushroom shape. The collaboration with Venini lasted for a couple of years and the result was an incredible number of lamps in a vast array of colors.

In 1965 Massimo and Lella co-founded Unimark International with five other partners including Bob Noorda, famous for his Pirelli-posters. Two years later they started a branch in New York. Unimark soon rose to fame through their corporate identities for, amongst others, American Airlines, Ford, Gillette and Knoll and it quickly became one of the biggest design firms in the world. Being on top didn’t last for that long though. In 1970 the Vignelli’s left the company to start their own business, Vignelli Associate.

The Vignelli’s eventually changed focus to product and furniture design and in 1978 they founded a new company, Vignelli Designs.

During their entire career the Massimo and Lella complemented each other with Massimo mainly focusing on 2D projects like the New York subway map and corporate identities for American Airlines while Lella worked more with their 3D projects.

They both lived by the motto “If you can design one thing, you can design everything” and in the case of Massimo and Lella Vignelli they really could.

A True Design Victim

As much as it is a piece of innovative design the Up chair was also a political statement. The design was inspired by an ancient fertility goddess and the ball and chain symbolizes women being prisoners, not a victim of design. “Women suffer because of the prejudice of men. The chair was supposed to talk about this problem.”

Born in La Spezia in 1939 Gaetano Pesce went to study in Venice at the School of Architecture and then the Institute of Industrial Design. After graduating he worked with collective of young architects in Padua before focusing on design from 1962.

Endlessly researching and experimenting with new materials he started working with the trendiest material of the day, polyurethane. Standing in the shower in his Paris apartment in 1968 Gaetano Pesce got the idea to try and make a chair behave like a sponge. In his workshop he realized that polyurethane was a perfect material not only for comfort but he could actually vacuum pack his new design. Opening the four-inch-thick package his new chair would almost magically expand into its proper shape rendering its name Up. This extraordinary and irreversible performance was made possible thanks to the freon gas present in the polyurethane blend.

This easily packaged and shipped future of furniture design unfortunately didn’t last long. In 1973, after only four years of international success with the Up Chair turning up in everything from the James Bond movie “Diamonds are Forever” to photo shoots with Salvador Dalì, the producer B&B Italia removed it from its catalog. This was due to a recent ban on freon gas making the production as it was impossible.

It took until the year 2000 for the Up chair to to make its comeback. This time being made in cold shaped polyurethane foam and no longer inflating.

Benvenuti a Venezia

Full of hidden meanings the Gondola Bow Iron is the things that make the gondola into a gondola. Every part of the decorative bow iron is there for a purpose. But let’s start with the gondola itself.

The origin of the gondola is lost to history but already during the 11th venture the distinctively narrow boat filled the canals of Venice. It was mentioned for the first time in 1089 and during the 1500s some 10,000 gondolas were used for transportation of people and goods.

The gondoliers were soon rumored to be a rough crowd that were gambling and extorting the people of Venice. This led to the upper classes buying their own gondolas and as the status symbols they were they started competing with color, ornaments and expensive fabrics. The gaudy luxury gondolas became too much for the authorities and in 1562 they made a decree that all but ceremonial gondolas had to be black.

The gondolas developed over the centuries but all of them are built in the special gondola boatyards called a Squero. The gondolas, being adapted to fit perfectly in narrow and shallow canals have no straight lines and one boat takes close to 500 hours. Many of those 500 hours was spent on the finishing touches like the many layers of water proofing varnish made from very secret family recipes. An important part of the gondola is the oar made by a Fórcola, an oar lock. Over the years they created the very intricate fork that you can see today. The fork is the holder for the oar that makes the gondolier able to move the oar in any number of ways. The gondola itself were continously modified and by the late 1800s the gondola makers started to make the left side of the gondola wider as a counterbalance to the gondolier. Today there are only around 400 gondolas left in Venice, compared to the 10,000 traveling the waterways 500 years ago.

The final touch on the gondola must be considered to be the beautiful bow iron or Fero da próva in Venetian. It is certainly there for decoration but every part of it has a meaning. The upper part symbolizes the hat of the Doge, the almost half circle under the hat is the Rialto Bridge and the open space under the bridge is the. The six rectangular shapes pointing forward are the districts of Venice. From the top, San Marco, San Polo, Santa Croce, Castello, Dorsoduro and Canaregio. The rectangle pointing backwards is Giudecca. The intricate shapes between the districts are the islands of Murano, Burano and Torcello and finally the whole shape from top to bottom is the Canal Grande.

Be Our Valentine

Time to spread some love again! Actually, maybe it’s about time to spread some lovin’, not only on Valentine’s Day but keep spreading it every day of the year, to friend and foe alike. This year we let the beautiful Bocca Sofa designed by the Italian Studio 65 in 1972 symbolize the day.

However you celebrate it, have a Very Happy Valentine’s Day!

And remember to make Each Day Valentine’s Day!

Sending the Bat Signal

The multi-disciplinary Gae Aulenti was born in Palazzolo della Stella, close to Venice, in 1927. She studied architecture at Milan Polytechnic University and graduated in 1953 as one of only two female students in a class of 20.

After graduation she worked as a graphic designer at a magazine called Casabella Continuita before becoming a professor at the Venice School of Architecture in 1960 and later at the Milan School of Architecture.

Apart from her career as a graphic designer, professor and architect Aulenti also gained fame as a furniture designer. During the 1960s she produced a great variety of furniture gaining her a prize at the Milan Triennial.

The Pipistrello lamp is essentially a very successful merge of two very different design elements. The streamlined telescopic base with the feel of American design and architecture from the 1930s and the lampshade made as a tribute to the natural forms of fauna and flora of the Art Nouveau movement.

Gae Aulenti designed the Pipistrello lamp in 1965 and went, sketches in hand, to Elio Martinelli who got famous in the 1950s for his innovative lamp-company Martinelli Luce. Seeing the sketches Martinelli immediately agreed to produce the lamp. Originally it was intended for the Olivetti store in Paris but it was such a success it was later put into production.

The smooth shape of the lampshade, looking like the wings of a bat, made Aulenti name it Pipistrello, meaning bat in Italian.

As an architect Gae Aulenti is probably most famous for the transformation in Paris of Gare d’Orsay to Musée d’Orsay. In 2012 she was honored when the Piazza Gae Aulenti was inaugurated in Milan’s most modern neighborhood.